Checkpoints: Laser-focused

Undersecretary of the Air Force Matthew Lohmeier ’06 shares his vision for strengthening the Air Force and Space Force

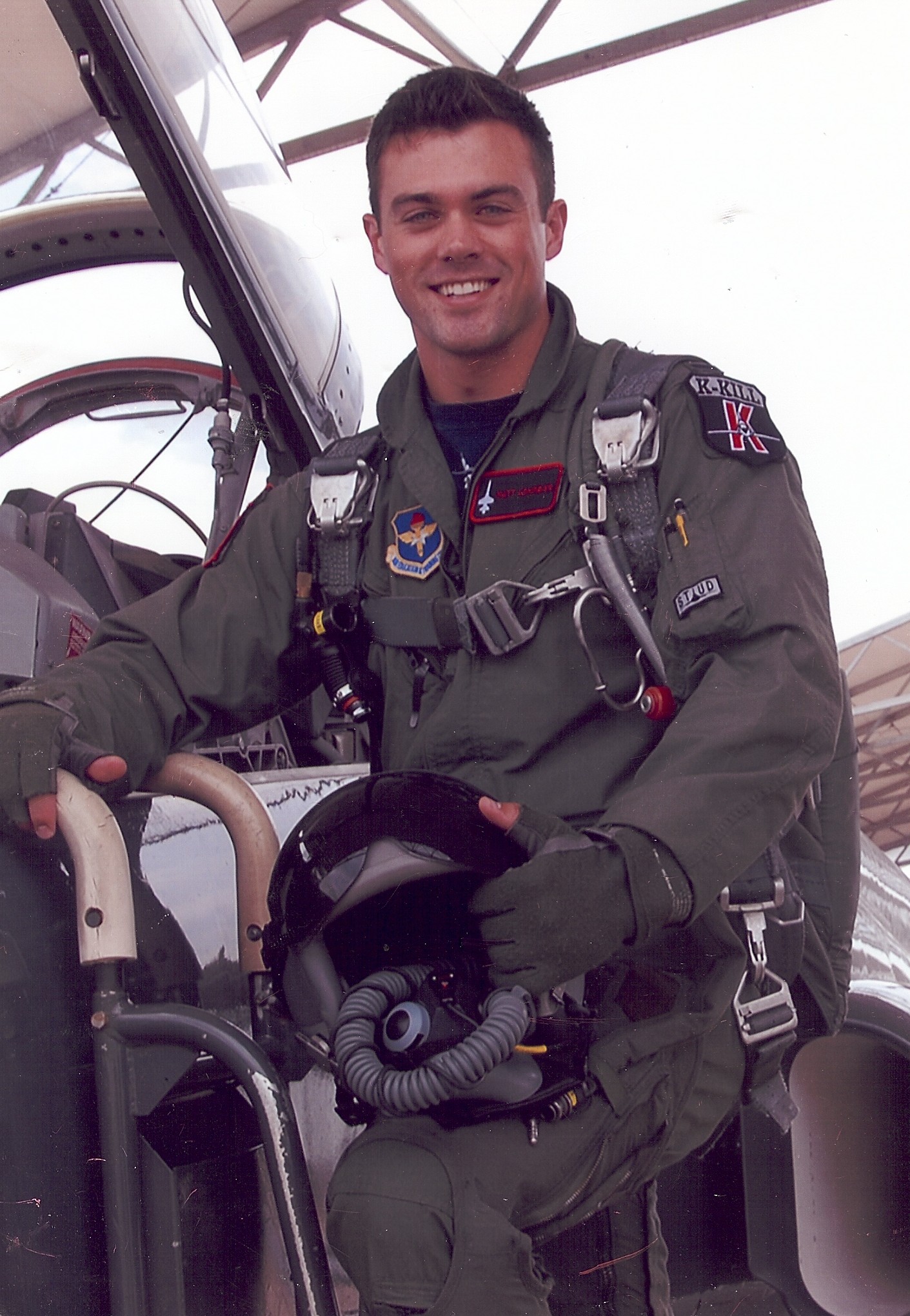

On July 24, the U.S. Senate confirmed the Hon. Matthew Lohmeier ’06 as the 29th undersecretary of the United States Air Force. He now helps guide the department’s strategic direction at a time of rapid change in global defense and technology.

Working alongside Secretary of the Air Force Dr. Troy Meink, the undersecretary helps manage an annual budget of more than $200 billion to support nearly 700,000 airmen, guardians and civilian employees. He has made it clear that servicemember welfare, force readiness and modernization are among his top priorities.

“Our airmen and guardians sacrifice a great deal to serve the American people,” Undersecretary Lohmeier said following his confirmation. “They deserve all of the best tools, training and support they need to perform their missions in an increasingly complex and quickly evolving threat environment. I’m honored to work alongside Secretary Meink in service of these great men and women."

The Department of the Air Force’s newest undersecretary recently returned to his alma mater and sat down with the Checkpoints team for a Q&A. The following is a lightly edited transcript of that conversation, which occurred Oct. 31.

What are your top priorities as the undersecretary of the Air Force?

My top priority is readiness. I’ve had many months to think about what those priorities should be, and they’ve admittedly continued to morph and develop over time. But spending the last several months in this seat has driven home the necessity of a focus on readiness, and I think that fits really neatly within the secretary of the Air Force’s priorities. He recently mentioned at the Air & Space Forces Association [conference] that he’s going to have a focus on modernization, readiness and people. And there’s always a tension between modernization and readiness, but I think you have to have a laser focus on readiness. We’ve got a trend that needs to be fixed, and it’s a readiness trend, and so that’ll be my primary focus.

You’ve served as both an airman and guardian. How have those perspectives shaped your leadership philosophy as undersecretary of the Air Force?

The air domain and the space domain are admittedly very different. They require a unique skill set and a unique mindset in each of those domains to successfully operate as warfighters in those domains. And yet, I think my leadership view or philosophy appropriately transcends specific military services and domains. What I mean by that is I think that any military leader, regardless of the domain they operate in, is required to possess — whatever their training was and whatever their skill set was — integrity, authenticity, care for other people and an ability to articulate the mission that we invest all of our time and energy into.

And whether I was in the Air Force on the one hand, or the Space Force, later in my career, the best leaders that I had, I thought had a good blend of those qualities, and the leaders that I thought had room for improvement somehow were lacking in those things. And my emphasis, in fact, while I’m the undersecretary and in working with all of our uniformed leaders, will be to emphasize things like integrity and authenticity and an ability to articulate the mission.

What do you believe are the biggest challenges facing the Air Force and Space Force in the next decade?

I’ve got a couple of ways to answer that, and I’ll start with where we began, which is readiness. Readiness is one of the biggest challenges the Air and Space Forces have. Part of that’s budget-related, of course, part of it is the competition between fielding new capabilities, modernization efforts and keeping healthy the systems that we already operate. Readiness is a perennial problem. It’s a challenge that the Air Force has had throughout its history. Of course, the older those systems get, the more difficult that challenge becomes. On the other hand, it’s the uniqueness of the character of war in the 21st century and the complexity of the threat that we face on the world stage. We are not just facing a single adversary at home or abroad. We’ve got a complex blend of competitors, adversaries, bad actors who seek to undermine the political sovereignty and legitimacy of our country. And all of our troops who sign up to put on the uniform and defend the Constitution need to grow into an appropriate, healthy understanding for the complexity of that threat. And I think one of the challenges that we’re going to have during this administration, as we come up with a new national defense strategy, for example, and the War Department continues to try and educate the force about its priorities, is to educate the force about the uniqueness of the challenges that we face.

Your background includes experiences in strategy, policy and operations. How do you intend to apply that strategic mindset to address the current challenges facing the Air Force and Space Force?

I had a good opportunity to — it was one of my favorite assignments — attend the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies. You mentioned strategy right out the gate. It’s a strategy school, and their approach to learning and thinking was to sit around a table and to discuss disparate views about things, ideas, books that we had just encountered as warfighters. When we come around the table and we discuss disparate views about what we had read, we would discuss unique ways of tackling the challenges that we face. And what that taught me in that environment, which was intended to produce strategists, was that it’s really important that we listen well to others’ views. We listen well to possible solutions, and we come to some consensus or unity about how we can tackle those challenges. We have a lot of challenges in the strategic, complex environment that we find ourselves in right now.

We’ve got the need to listen to unique and innovative solutions to the problems that we face, and absent that listening, I don’t think any amount of experience in strategy or policy or operations is really going to help us much. We have to find ways as a team to come together and find innovative ways to tackle these challenges. And I think we’ve got an excellent leadership team, at least in the Department of the Air Force, because that’s who I work with most closely, of course, but really across the entire joint force, from what I can tell, who are aware of the need to listen well to one another and find great ways to enable the entire joint force to be successful in this new threat environment.

You’ve emphasized the importance of service member welfare and service culture. What are your top priorities to support the well-being of the 700,000 airmen, guardians and civilian personnel under your care?

I’m going to echo something that Secretary Meink said — again, at AFA [Air & Space Forces Association conference]. Because of the uniqueness of the threat environment and because of the complexity of the capabilities that we are fielding, I think we have the challenge before us to provide adequate training to our warfighters to operate those capabilities and to operate within a rapidly evolving, technologically dynamic environment. And so providing all of our people the right training and the right tools that they need to succeed, I think, is going to be tremendously important. So you do what you fund, and you have to think through and talk through and listen to the challenges that we have there, and then you fund appropriately the tools for our warfighters to make sure that they can succeed.

One of the things I saw on, I think it was day one or two of being in the seat, I got a briefing on Operation Midnight Hammer. I saw the great work that our airmen and guardians are capable of accomplishing when they have the right tools and the right guidance. And I don’t doubt their ability to accomplish any mission on the world stage. I do doubt, however, a bureaucracy’s ability to always provide them what they need to be successful. So when you get the right leaders in the right seats who are able to work as a team to provide them those tools, I think our airmen and guardians are capable of tackling just about any challenge that they’ll face.

How will you work with the secretary of the Air Force, the chief of space operations and the next chief of staff of the Air Force to implement key policy decisions?

It's important that we work well together. And for the record, I’ll say, Secretary Meink and I work very well together. I’ve been in the seat for several months. We communicate clearly and often, and we’ve had a bit of a lag in getting an entirety of Air Force and Space Force uniformed leaders into the seat, but just recently, had our new chief of staff of the Air Force confirmed, and a new vice chief is on the way shortly, I hope. And it’s been great in the few months that I’ve been there, working with Chief of Staff of the Air Force [Gen.] Dave Allvin ’86, who’s retiring, but the “how” comes in the unity that the civilian and uniform team are going to bring to the fight, and knowing the relationship I’ve got already with the Space Force team and with Secretary Meink, I fully anticipate that once our new chief of staff and vice chief of staff of the Air Force are in place, we’re going to be completely synced up with our priorities, and then it’s just a problem of communicating that well to the force, and it’s about selecting the right leaders and enabling them to communicate that to the force. And I have no doubts that we’re going to be able to get that right. One other point I want to make: I happen to know that our new chief of staff, [Gen. Ken] “Cruiser” Wilsbach, cares a great deal about readiness. I’m really happy to know that that’s been a focus of his while he was the commander of Air Combat Command, and I believe he’s going to bring that focus into the Air Force as the chief of staff, and so our priorities already align very nicely.

What specific modernization efforts do you believe are most urgent for maintaining technological and operational superiority in air and space domains?

Which modernization efforts are most important is almost like asking which of my children I love the most. There’s a lot of exciting things we’re doing. There are some that come to the forefront of just about everyone’s mind when you get a question like that — the new F-47 is an exciting program. The president’s announced it. It’s going to fly before the end of this administration, I think. It’s going to bring an absolutely essential capability, from a power projection perspective, into the Pacific that we need, and that’s chief on the list. There are other capabilities, of course, that come with that, or that complement the F-47 — the collaborative combat aircraft, of course, fits into the answer, because it’s an exciting complex next-generation capability as well that helps us integrate our long-range kill chain. And I’ll say that there are some exquisite — I hate throwing that term around too much — and exciting space capabilities that we’re trying to field as well that don’t get the attention that the air capabilities often get. We’ve got a lot of impressive, exciting things going on in space. And there was a point that was driven home to me recently. I went to an air show out at Andrews Air Force Base about a month ago. Everyone in the world wants to show up in air show and pet airplanes and watch them fly low and fast and perform their maneuvers. You can’t do a lot of that with our space capabilities. And so that’s an arena that I think requires a bit more education effort. We need to better articulate what it is we’re doing here, and we’re working on that, but we’re fielding capabilities, as Secretary Meink pointed out at AFA, right now in space that didn’t exist five years ago, and so there’s a lot of developments there that I think are going to be absolutely critical for our success in maintaining our advantage on the world stage.

What lessons have you learned in leadership since taking on this role that you wish you knew earlier in your career?

I think it’s important as a leader to listen well. When you can, and have the time, suspend judgment when there’s a lot on the line, especially when decisions can be fraught with emotion and a lot of parties are involved. It’s really important to take time to gather data, to listen to all parties involved, to sleep on some things when you can afford to do so and, especially when it comes to senior leaders in the Air Force.

Now [when] making decisions, if and when possible, you have a united front that’s able to come to a mutual agreement about the decisions that we’re making and then throw our full weight behind that in communicating that to the force.

My sense is, the reason I’m answering the way that I have is because, in part, my sense is that we’ve been through a transition period here for about a year, and I haven’t been a part of the Air Force that entire year. But I think that what we’ve had is, people have felt like they’re in limbo. There’s been a period of transition in which there’s been a new politically appointed civilian leadership that’s come in, and a lot of decision making has been suspended in the interim. The force needs clarity from leaders on the direction that we’re pursuing, and as we get a unified leadership team finally seated, I think we’ve had the time and data to reflect on the direction we want the force to go. And now throwing all of our weight behind that and clearly communicating that’s going to be really essential to the success of the entire force. There are some pretty weighty decisions that are being made, and no one person is going to make any of those decisions. There’s a leadership team for a reason, and there’s a uniform and a civilian component to that, and we’re all listening well, and we’re trying to be very thoughtful and deliberate about some of these critical decisions that we’re making that are going to impact the country for many years to come, and they certainly imminently impact the force, the people that serve in uniform.

And so we’re trying to get those things right, but as long as it’s taken for some of those decisions, once we move out, we move out with alacrity, and we throw our full weight behind that, and that gives a sense of security to the troops that are actually working these programs, the problems, the training that they’re involved in on [a] day in and day out basis. And oftentimes, I’m aware that they feel like there’s some thrash and that they’re at the end of a whip. And you can’t have that. You need to minimize that.

And I will say this too: Intuition cannot be neglected. Judgment, gut judgment — that’s what I mean by intuition — shouldn’t be neglected as thoughtful as we need to be, as deliberate as we need to be, as serious as some of these decisions are. When you get the right leaders in place at the local level, for example, I want them to have developed their sense for their mission and their people, so that they can make intuitive decisions with speed and take risk and move out. And that’s why we pay them the big dollars, because I know they do exceptionally important work. That’s why we trust them with leadership. That’s why they’re in command.

What inspired you to attend the U.S. Air Force Academy, and how did it shape your career path?

I was recruited to play basketball at the Air Force Academy. I didn’t know there was an Air Force Academy until I was recruited to play basketball. God saw to it that I had the best basketball games of my life when the Air Force coaches were watching. I had some of the worst games of my life when other coaches were watching. And so it seemed it was destined that I’d come this direction. But what inspired me to come here was, first of all, a really exciting exposure to cadet life. They didn’t show me much of the four-degree life. They showed me the football games and the rigor of the academic program here. And they foot-stomped integrity and “we do not lie, steal or cheat.” That was driven home while I was a high school student when I was first introduced. And the sense of purpose that cadets are initiated into when they go through basic training, that was really appealing, even to a young man who never had ambition for military service. I didn’t have parents that served.

Once they hooked me and I got here, then the question becomes, what kept me interested in an Air Force career? And it’s the same answer: It was my belief in the values that the institution was trying to instill in me as a young man, and I’ve shared publicly elsewhere, that, you know, I really learned to be honest while I was here, really for the first time in my life. It’s not that I didn’t care about those things before I came here, but that there’s enough preaching that goes on here, so to speak, and enough good examples here that you, if you’re willing, learn to take it seriously for the first time in your life, and I did, and it shaped who I was. I left one world behind. I came here to the wood between the worlds, to use C.S. Lewis’s phrase from The Chronicles of Narnia. This was a place of transition for me between worlds. And I left here and commissioned and went out into a new world, which was a commissioned officer in the Air Force, and I was a different person for it. And so I was inspired at first, because of the values that we teach here.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced as a cadet?

The biggest challenges, you know, they strip everything away from you when you come here. Every young four-degree recognizes that when they come here, you lose some bit of your liberty. You get your hair taken from you in the first place. You get all your clothes taken from you, and you get a new set of clothes. And that’s hard. It’s hard to set aside what you perceived was your freedom to act and move and to speak freely, and you leave some of that behind to come here. It’s all for good purpose, of course, but those are the biggest initial challenges. You get that back, of course — the more lasting lessons that you learn are something that you only get after a whole four-year experience here. And it wasn’t until I left here that I got to reflect on the difficulty of this place that I grew to appreciate it the most.

What was bitter at one time, and I’ll tell you a lot of the time you come back from a Thanksgiving or a Christmas break, it’s bitter to return to the Air Force Academy. It’s difficult here, and all of that bitterness, put it that way, that’s the word that comes to mind, but the difficulty, the trial of the Air Force Academy, is somehow turned sweet with each passing year as you reflect on the experience that you’ve come through. It was the same thing I went through a SERE training. It’s difficult. What challenges, what opportunities did you have there? Well, you don’t really enjoy it when you go through survival, and evasion, and resistance and escape, you just don’t, and you get through it, and everyone goes out for dinner and talks about the thing they’ve just been through. And the more time you reflect on it, the more grateful you had the experience. You develop lifelong friends here, and you’ve been through the same hard things together, the same kinds of things. This is an incubator of sorts, the same kinds of things you go through here, on a much more serious scale, you’ll go through as an officer at some point, leading troops in the Air Force or in the Space Force. And we’ve got real-world missions that we go out to lead, and something deep inside of you draws upon what you experienced here at USAFA and you’ve become more capable because of the leadership laboratory that is the Air Force Academy.

How did your time here at the Academy prepare you to lead throughout your career?

One way in which I think the Academy prepared me to lead when I left was that I had a few examples of other leaders from my time at the Academy who I tried to imitate. I’ll share one example. For some reason, it’s an unlikely example. I don’t know why, but it was my cadet squadron [air officer commanding]. He was a helicopter pilot. I was the cadet squadron commander, I’ll add in. And we were getting ready for an inspection, some inspection that you get ready for on a weekend, and we’re all making our beds, and we were folding our socks, and the cadet squadron AOC came in asked how my prep was going for the inspection. I was living by myself; I didn’t have a roommate at the time that I was the cadet squadron commander. He said, “How’s your prep going?” I said, “It’s going great.” I was pretty satisfied with my progress. I thought I was going to be an impressive example to the other cadets of just how put together my room is. He said, “How’s everyone else’s preparation coming along?” I said I didn’t know. And he asked me, “Why not?” He says, “What’s your job here?” I said, “I’m the cadet squadron commander.” I was pretty proud of that. And he says, “How come you don’t know what the progress of the others is?” And I didn’t have a good answer. And he says he thought about going to help them. And I said, “Yeah, maybe when I get my room put together, I’d be happy to go help other people.” And he says, “What do you think of this idea of service before self?” And I didn’t even think I agreed with his approach of like leaving my stuff behind to go help others. But he asked me then, because I knew he could tell I wasn’t buying in, he asked me if I’d consider stopping what I was doing to go help others.

First, I was bothered by it. Actually, I thought it was the wrong order of things. I needed to get my own house in order before helping others. But he basically held my hand, so to speak, and walked me down the hall, showed me what it looks like to check in on others, make sure they’re getting ready before I took care of myself, and it’s been 21 years, I think, since I had that conversation, and I’ve reflected on it probably at some point every single year since leaving USAFA.

Again, to this day, I don’t know if I had the order right there, but he was trying to drive home a point, and it’s the idea of service before self, and I didn’t know what the status of the other people in my unit was. All I knew was how well I was doing on what I was working on. And I’ve occasionally had opportunity to reflect on whether or not I’ve got that priority right. Do I know how others are doing in my unit? When I thought about it, when I was a squadron commander of a space-based missile warning squadron, how are my people doing? It does no good if I think I’ve got all of my ducks in a row, but I don’t know how my people are doing, and so I had to ask myself, “How are they doing? Is there anything I can do to help them?” And I’ll worry about some of my needs later.

You can’t always get it in that order, but something about the way in which he approached me — and he knew how to approach me about this — really struck a chord with me. And I think, at USAFA, you’ve got an opportunity as cadet squadron air officers commanding; you’ve got an opportunity as cadet squadron leadership. We’ve got an opportunity as senior enlisted leaders at USAFA to influence very moldable young men and women who are 19 and 20 and 21 who are going to be future leaders of our Air Force. We have great ways, great opportunities, to influence them and teach them what it means to be men and women of integrity and to serve others before themselves and be excellent in what they’re doing in ways that we just don’t have anywhere else in the Air Force. This is a unique incubator, and so [I’m] really grateful for that time I had, and I’m sure that all of our cadets, many of them, if they’re applying themselves, have that same opportunity today.

If you could go back in time and offer Cadet Lohmeier advice, what would that be?

I don’t know if my answer will be satisfactory because questions like this are just really tough for me. We all make good decisions and bad decisions. We all look back and wish we could have done something differently. For example, I was in the end a social sciences major. There have been many times that I’ve thought I should have taken advantage of the aeronautical engineering program, for example, or done physics. I study that stuff for fun in my free time now, and I can honestly say I’ve thought about regretting the decision to pursue the path that I did while I was here, but I don’t regret any bit of my journey. There [were] good times and there were bad times, and they’ve all been an important part of my life journey.

I think the healthiest approach would be, I could go back and pat myself on the back and say, “You’re on the right path. And however hard things become each year, it’s OK, because it’s all a part of shaping who you’re going to be.” And if people have the right mentality, however many tours they march, or how many ever difficult classes they get in trouble with, or however high they think they’re flying while they’re here, things are going to change, and the wheel of fortune keeps turning, and you can’t always control the good and the bad that’s going to come your way, but we ought to reflect in gratitude on the things that are shaping us. And, so, I don’t know if I would try and encourage the old me to change anything about my path. I’d simply encourage me to press on. “You’re going to get it right and keep your values intact. The things you’re learning here are correct — meaning integrity, service and excellence — and if you keep those things dialed in, come hell or high water, there’s going to be a way through. You’ll be able to rely upon your peers to see through any challenge, and you’ll be able to make a positive impact on the world stage.”

What qualities do you believe Academy graduates must have today to meet the demands of modern service?

I’ll beat this drum happily for my entire time that I’m the undersecretary. And it’s integrity, service and excellence. This is the unique laboratory that trains cadets [that] those things really matter. In fact, I plan to talk more about them as the months go on, because integrity isn’t just doing the right thing when nobody’s watching, it’s doing the right thing when everyone’s watching, and they don’t necessarily agree with you. And it’s somehow continuing to develop your character and then aligning your speech and your thought and your conduct outwardly with the inward conviction. And the Academy can do that exceptionally well for our future leaders.

After nearly two decades in uniform and a career as an author and speaker, what motivated you to return to federal service in this high-level civilian role?

I’ll say, probably more than anything, a sense of duty, because I was very happy to be a private citizen. Being perfectly candid about it, I didn’t have ambition to return to government service, but the president asked me to serve, and I was happy to do that. And I believe in the direction we’re going as a department — we’ve got exceptionally challenging decisions that we’re facing and we’ve got a uniquely complex threat environment, as we’ve discussed earlier, and there is a real part of me that would actually like to leave to other poor souls to face those challenges and make the hard decisions and to enjoy private life as a citizen.

That’s why the state exists in the first place. It’s to protect the citizens so they can enjoy their private affairs.

Now I very much enjoy private affairs. I just went to Mount Vernon with my family recently and heard that George Washington was always seeking the next opportunity to get back to Mount Vernon and to tend his garden and to take care of matters at home, and yet was willing, out of a sense of duty, to serve the people. And in whatever small sphere of influence I have the opportunity, at present to occupy, it’s a sense of duty that draws me back into public service and I’m happy. And having said all of that, and being candid about all of that, I’m genuinely happy to be here and really like the people I’m working with in Air Force and Space Force senior leadership. They’ve got their priorities intact. They’re really trying to serve the men and women in uniform. I like working with Secretary Meink. The country should be grateful to have Secretary Meink as the secretary of the Air Force. He’s exceptionally bright. He’s very clear-eyed about the challenges we face, and he’s very thoughtful in his approach to how to solve those problems.

So I really couldn’t have asked for a better team of people to integrate into to do this job, which just sweetens the deal when I’ve made the decision ultimately to be a public servant. And having said all of that, I really do look forward to the chance to return to being a private citizen someday and turning over the reins to other people and yet understand that there’s always the possibility that you’re asked to be a public servant in other ways. And so you weigh that, and you see if duty calls you to other directions.

Anything else you’d like to add that we didn’t touch on?

I’ll foot-stomp something that we’ve already talked about and it’s integrity. Something about that is deeply important to me. I suppose what I’ll say about it is I’m grateful for the Air Force Academy experience, as hard as it was, as bitter as it was, to return year after year. I really believe in the program. However, it’s changed over the years, whatever nuance that any leadership team brings to the Academy program. I really believe in what we’re doing here, so I want to cheer on all of our cadets [to] learn earlier in life than later that your integrity matters, because it’s something that even after you put down the uniform, you will take with you the rest of your life, and you can do great things in your sphere of influence if you’ve got your integrity intact, and you can destroy a great many things if you don’t.

And so I want to share that, and if there’s anything I leave behind as a legacy — I’m at the very beginning of my tenure — but I really hope to beat this drum early and often, so that when I leave someday, people recognize that I actually focused on integrity while I was here, and authentic leadership that’s fueled by integrity.