Checkpoints: Taking flight

USAFA grads navigate the high-stakes world of IPO's

Times Square pulsed with afternoon crowds streaming past honking taxi cabs and street vendors. Matt Kuta ’05 stood in the middle of it all. His team huddled around him as he raised a bottle, his thumb working the cork. It exploded upward with a pop that turned heads, champagne shooting into the air as Voyager Technologies supporters applauded and roared.

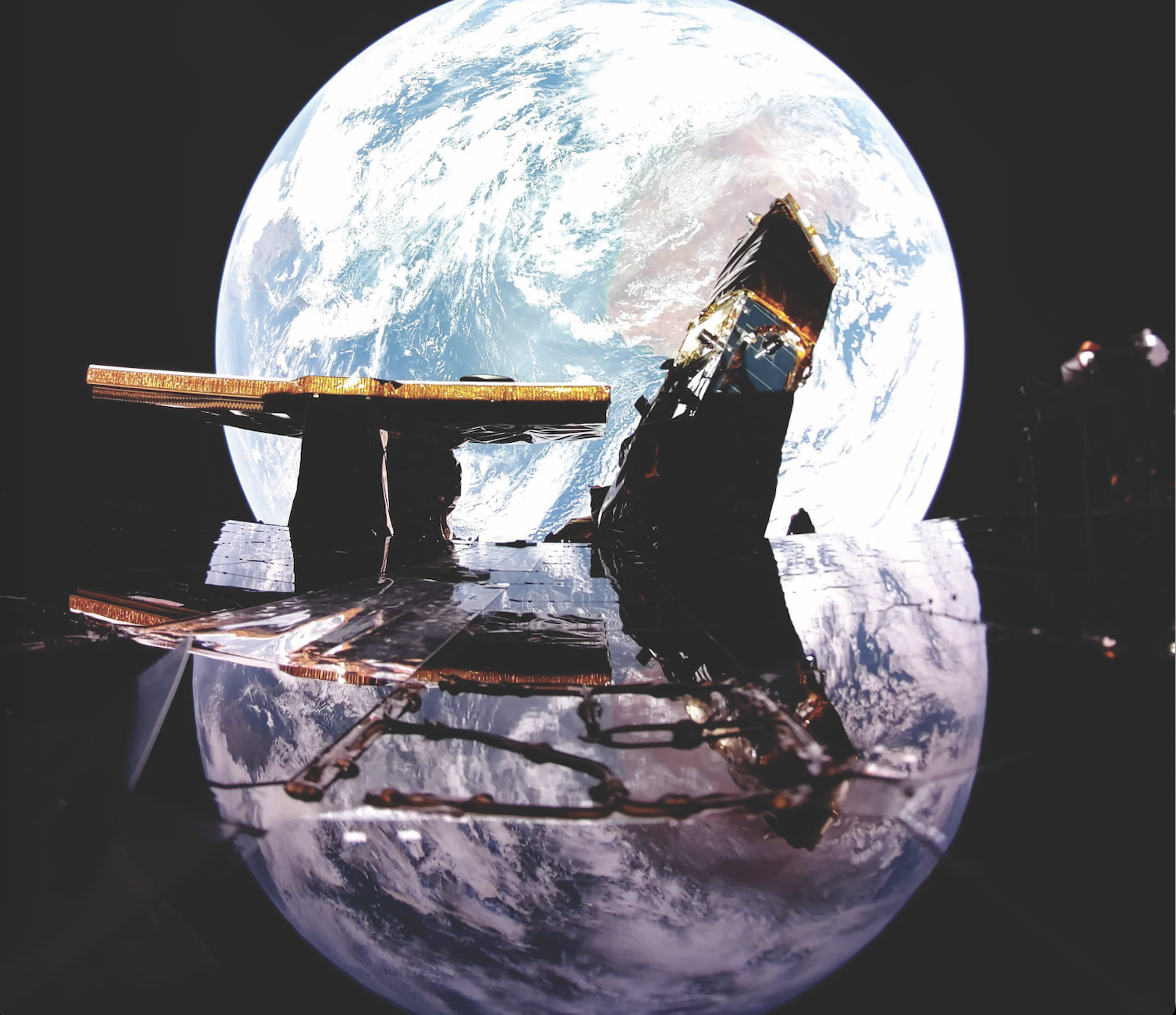

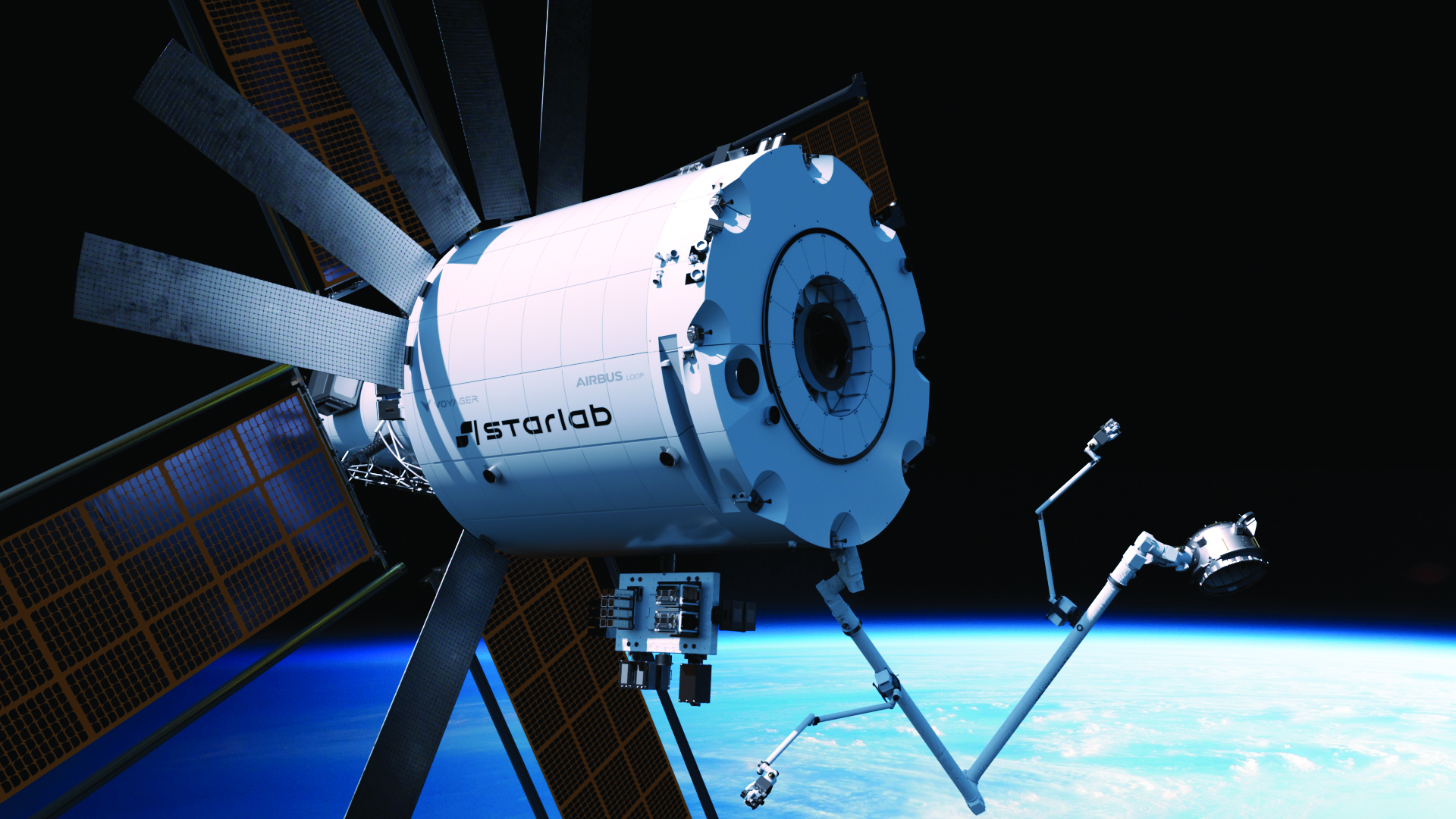

Above their heads, a jumbotron the size of a multistory building blazed with an image of Starlab, the commercial space station that Voyager is building to replace the International Space Station orbiting 250 miles overhead. Hours earlier, Voyager co-founder and president Kuta and CEO Dylan Taylor stood flanked by their executive team as they rang the New York Stock Exchange’s opening bell, marking the company’s debut as a publicly traded corporation.

“It is really surreal to think back that we started a company with no money, no revenue and no employees — just an idea in a PowerPoint presentation,” Kuta says. “We started Voyager six months before COVID, and then we had interest rates rise and two land wars kick off in Europe. To look back on everything that the team accomplished and be able to successfully have a traditional IPO on the New York Stock Exchange is quite the milestone.”

From Silicon Valley boardrooms to Wall Street trading floors, U.S. Air Force Academy graduates are helping shape — with integrity, service and excellence — one of capitalism’s most critical moments: taking companies public. Whether as founders ringing the opening bell, investment bankers orchestrating billion-dollar debuts or early-stage investors spotting the next breakthrough, these graduates bring leadership to an arena where thousands of jobs hang in the balance. The path from the cockpit of a fighter jet or acquisition office to IPO isn’t obvious, but the skills forged on the Terrazzo and in operational assignments translate remarkably well to the high-stakes world of public markets.

FROM COMBAT MISSIONS TO MARKET DEBUTS

The ability to lead under pressure, execute complex missions with precision and maintain composure when things go sideways makes Air Force Academy graduates uniquely suited for the controlled chaos of taking a company public.

For Kuta, a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross and Jabara Award winner, the pressure of an IPO paled in comparison to what he experienced leading combat missions in the F-15E Strike Eagle. Flying almost exclusively at night over Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria, he performed high-risk maneuvers like night low-illumination strafing while supporting troops on the ground.

“In combat, the pressure is making sure I’m going to bring my guys home,” Kuta says. “When I pushed the ‘pickle button’ to release a bomb for the first time in Afghanistan during a troops-in-contact, I had this knot in my stomach because you won’t know until the bomb goes off whether you did everything right.” That perspective serves him well when navigating the unpredictability of Wall Street. When a company goes public, the executive leaders don’t know for sure until the night before whether the offering will price at a sufficient level and raise enough money to proceed. Family and friends are already in town, employees have gathered and the pressure builds. “During the IPO process, some of the investment bankers and lawyers said, ‘You seem so calm, so unflappable,’” Kuta recalls. “I’m like, ‘This is just me. Everything’s going to work out. If it doesn’t, the world’s not going to end.’”

Jason Kim ’99 echoes that sentiment. As CEO of Firefly Aerospace, he led the company through the largest space IPO in history in August, raising nearly a billion dollars just months after Firefly became the first commercial company to fully successfully land on the moon. For Kim, watching his team celebrate that historic moon landing in the Mission Operations Room stands as a proud moment he will never forget. Firefly’s Blue Ghost lunar lander touched down upright and stable — a feat only five countries had accomplished before Firefly — and then conducted the longest commercial surface mission in history at 14 days. “It showed all the hard work, all the sacrifice, all the smart thinking,” Kim says. “All the simulations and rehearsals that the team did over many months came to fruition with something that was world-inspiring.”

THE BANKER'S PERSPECTIVE

While founders like Kuta and CEOs like Kim experience IPOs from center stage, investment bankers orchestrate the complex logistics that make those moments possible. Lt. Col. (Ret.) Bobby Wolfe ’99, who serves as a director and global head of cybersecurity investment banking at his firm, has advised many industry-leading companies through some of the sector’s most high-profile public debuts and transactions. The work starts well before the opening bell. Bankers help draft the prospectus, meticulously craft management presentations, hand-select investors, coordinate coast-to-coast roadshows, build order books, allocate shares and debate the right price. “While everyone loves the sound of the bell and pictures from the first day of trading on the floor, it’s all about logistics,” Col. Wolfe says. “The banker’s job of managing the IPO process and providing critical advice starts months in advance. Each IPO brings back memories of long days and nights with founders, investors, board members, lawyers, fellow underwriters and company executives. It’s a hectic and exciting time with a lot that goes on behind the scenes, but it’s only the beginning for a public company.”

Col. Wolfe retired in 2019 after serving more than two decades in the Air Force across active duty and the Reserve while building his banking career. He found balance through flexibility and, as he puts it, very little sleep. His path wasn’t traditional. After earning his Harvard MBA in 2011, he started at the bottom, entering banking as an associate without a clear career trajectory. His transition from military to Wall Street came with more than a few culture shocks.

An early boss — the global head of his group — was adamant that business is done on a first-name basis, which was the opposite of everything he had learned in the military, and nonchalantly threatened to fire Col. Wolfe for addressing a client as “sir.” “He may have been joking, but that was an eye-opener and a hard habit to break,” Col. Wolfe says. The software IPO landscape has evolved dramatically since Col. Wolfe entered the field. Early in his career, software companies could go public before reaching $100 million in revenue, sell $100 million in stock and target a $1 billion market capitalization. Today, companies are materially larger, often above $300 million in revenue, can sell $500 million to $1 billion in stock, and can likely expect a $5 billion market capitalization on Day 1. What makes software companies attractive to investors is their business model, which provides recurring revenue that gives investors visibility into the future, strong gross margins and key performance indicators around customer retention that other sectors struggle to replicate. “Software companies today are attacking huge markets and are efficient at the gross-margin level, and software companies often disclose metrics, such as annual recurring revenue and customer retention, that other sectors may not be able to disclose,” Col. Wolfe says.

The moments before pricing an IPO test everyone involved. The roadshow runs about two weeks, with bankers shuttling management between meetings, investor calls in cars, presentations, meals and flights, while the CEO and CFO stay constantly on the go working to balance running the business back home. “Everything culminates when the underwriters present the stock purchase order book to management and actually price the IPO the night before the stock starts trading,” Col. Wolfe explains. “That pricing meeting usually occurs in a nondescript conference room at the top of a New York City skyscraper, and everyone is exhausted. The next morning is a blur as the company rings the bell and starts trading, followed by a full sprint with reporters, talk shows and news outlets. Throughout that first day, everyone watches every minute movement of the stock.”

Through it all, bankers serve as trusted advisers. The best bankers play a unique role as a key partner to decision-makers, executives and investors in an industry. “Investment bankers monitor, track and transact in the capital markets every day,” Col. Wolfe says. “From that unique vantage point, investment bankers can provide perspective, serve the ecosystem and shape the landscape of industry for years to come.”

SPOTTING WINNERS EARLY

Paul Madera ’78 — namesake of USAFA’s Madera Cyber Innovation Center and a Distinguished Graduate — sees companies long before they’re ready for Wall Street. As managing director at Meritech Capital, he co-founded one of the first firms focused specifically on late-stage venture capital. When he started in 1999, the firm raised the first billion-dollar venture fund, though he’s quick to note it was their worst-performing fund, given it was invested at the height of the tech bubble. But that experience helped validate the concept of later-stage venture capital and launched a career that continues today.

“All the training and practice with flying fighters is focused on one thing: getting to the target or the area on time and employing whatever you have effectively,” Madera says. “That’s really similar to what I look for in companies today.” Madera searches for companies with interesting early traction, business models that work, gross margins that make sense, and measurable sales and marketing efficiency, but the human element matters most to him. “These entrepreneurs tend to be particularly smart and charismatic in terms of recruiting other team members,” he says. “They’ve got huge goals and have this determination that presses on even when all their family and friends say, ‘No, it’s crazy, don’t do it.’ We actually like to see those, particularly when they’ve gotten a little bit of traction and they’re headed down the right path.”

When Meritech invests, companies are still five to seven years away from going public. Software companies need several key elements to be IPO-ready. First, they must approach $300 million in annual revenue to near profitability. They also need to maintain at least 20% annual growth while demonstrating clear business models with strong gross margins and efficient sales and marketing. Finally, their market must offer a significant runway to sustain this growth for several years. Madera’s role is hands-on but measured, and his firm never replaces management of successful companies because there’s a magic element they haven’t figured out themselves. Instead, they act as counselors around the edges. “A lot of these entrepreneurs tend to be brilliant engineers who haven’t managed many people,” Madera says. “They’re in a very lonely job. They’ve got to put up a front of success and confidence to their team. We seek to be counselors, providing guidance, helping with introductions to round out the team.”

Madera says one quality gained from military service proves invaluable in what he does: the ability to work with anyone. In the military, you don’t get to pick who you work for, how long you’re in a position or what job you’re given, so you just make it work. “You develop an ability to work with all kinds of people, which is different than most civilians,” Madera says. “In the civilian world, [if] you don’t like your boss, you quit and go somewhere else. The military says you’ve got to get through, keep your eyes on the target, keep your eyes on the mission and do it. That tends to be a really helpful quality in my world.” Madera sat as a board observer at Facebook from 2006 to 2012, watching the social network’s development through its IPO. The investment almost didn’t happen, as Meritech was negotiating with MySpace when that company was sold to Fox Interactive. They pivoted to the next-best option: a startup with 30 colleges on its platform called Facebook.

The path to success wasn’t obvious, as most investors were ready to sell for a modest gain. At one board meeting, it was revealed that Facebook was spending four times as much supporting each account as they could generate in revenue, and the advertising model on social networks was unproven. “Thank God we hired Sheryl Sandberg [a technology executive who served as Facebook’s chief operating officer from 2008-2022] from Google,” Madera says. “She brought real business savvy that made it work.” Over 26 years investing in tech companies, Madera has learned humility, as no one gets it all right. He points to Netflix, HubSpot, Uber and DoorDash as examples of companies he missed. But Meritech did manage to invest in Salesforce, Datadog, Roblox, Coupa, Flock Safety, MuleSoft and 10x Genomics. The key, he emphasizes, is having a framework and sticking to it rather than chasing every deal. “We look to have a screen in our business that is high enough that we’re going to miss several that end up being successful,” Madera says. “We don’t want to be in every company. We just want to be in companies that work.”

Today, the biggest trend reshaping venture capital is artificial intelligence. Currently, more than 50% of all venture capital is invested in AI, Madera says, and it could change the world as much as the internet did starting in 1998. But it’s also incredibly early in the development of AI-based companies. “Many of these companies who are raising tens of millions, if not billions, of dollars, don’t really have a fully fleshed out business model yet,” Madera says. “So there’s a huge maelstrom of activity and investment that is just not very clear where it ends up, and it’s going to be fascinating to watch.”

BUILDING THE FOUNDATION

Samantha Sarkis ’11 works even earlier in the investment cycle. As a vice president at Atlantic Pacific Capital, one of the largest independently owned private equity placement and advisory firms, she helps raise capital for private equity, private credit, real estate and other alternative investment strategies not accessible to typical retail investors. The money she helps raise comes much earlier than IPO capital and gives companies resources to grow by recruiting talent and pursuing mergers and acquisitions that make them more attractive candidates when they eventually go public. “I think the capital that I get to help raise helps build the foundation for them to get there,” Sarkis says.

Her path to finance wasn’t linear. Growing up in Minnesota, she was recruited to play tennis at the Academy and drawn in by the opportunity for a top-tier education and a nontraditional path. After graduating, she served as an acquisition officer managing procurement and sustainment programs on large cargo planes worth tens of millions of dollars. Balance didn’t come easily at the Academy. Her freshman year GPA was 2.7, and she felt overwhelmed by everything coming at her.

Sarkis turned the corner when her adviser told her about a corporate internship program requiring a 3.0 GPA. She stepped back from tennis after her three-degree year, and once she took something off her plate, her GPA immediately improved to a 3.0 and above, placing her in the top 10% of her class academically by graduation. “I think the lesson really is you can’t do it all; but if you prioritize your time and fully commit, you can excel and things can really take off,” Sarkis says. The transition from Air Force acquisition to equity capital markets at Bank of America, she says, humbled her. “You go from managing teams, and then you get put at the bottom of the totem pole,” Sarkis says. “Even though I was an associate, I was placed at the bottom with all the analysts. It was jarring, but it taught me to prove myself all over again.” It was even harder because she started in March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. What would normally be on-the-job training became clunky Zoom screen-shares showing Excel models, data searches and file hierarchies. The steep learning curve stretched longer.

The saving grace was starting through a small veteran cohort rotation program, where everyone felt the same pressures and leaned on each other. At Bank of America, Sarkis joined the equity capital markets team, which advises companies on raising capital through the public markets, including IPOs, follow on offerings, convertible bonds and block sales. When companies want to go public, coverage bankers will bring in the equity capital markets group to advise on timing, size, target investors and positioning of the story. One aspect she loved was “testing the waters.”

Before a company goes public, the banks working on the IPO arrange practice meetings, where management pitches their story to potential investors. Sarkis’ role was to follow up with investors afterward, calling to understand their real concerns and reactions, and then translating that feedback into actionable insights the company could use to refine their messaging and address investor hesitations. She loved this investor relations work but wanted to move away from the demanding market hours, and Atlantic Pacific offered the perfect intersection: storytelling, relationship building and entrepreneurial agency over her work. That relationship-driven approach now shapes how she evaluates opportunities.

When considering whether to take on new mandates, Sarkis looks at team, strategy and track record. The team’s background and experience must authentically align with what they’re doing. The strategy must offer clear differentiation in a crowded field. The track record needs to demonstrate consistent performance with minimal blemishes. One trait proves surprisingly important: marketing ability “If a team is strong at telling their story, it goes a long way,” Sarkis says. “Management teams shape the first impression, and that narrative strength can sometimes offset weaker areas in the pitch.”

She says the most challenging aspect of her role is capturing attention and mindshare, as investors in New York receive hundreds of emails per day. Breaking through that noise requires close relationships where you can call and get an answer. Sarkis credits her Academy training for preparing her for capital markets, as the cross-functional structure mirrors her work environment. Juggling multiple projects under pressure became second nature through years of balancing academics, athletics and military training. “Operating in the military on high-stakes missions gives you perspective,” Sarkis says. “It teaches you how to stay composed when the stakes are high. So in this industry, even when the work is intense, it never feels unmanageable. I know I’ve handled more demanding situations before.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

The IPO market is opening wider than it’s been since before COVID, and companies that have been preparing behind the scenes are seizing the moment. For defense and space companies in particular, investor interest is surging. Voyager’s IPO demonstrated that appetite, as the company initially targeted a price range in the upper $20s per share. Strong demand during the roadshow pushed the stock price to $31 at IPO — above the initial range — and Voyager also increased the amount of capital raised beyond the original target to roughly $400 million. “We did the roadshow, and because we had so much interest and demand, we increased the share price and increased the amount of money we raised,” Kuta says. “I think we opened the IPO window for some of the other companies that chose to follow us shortly thereafter.” Starlab, the commercial space station that Voyager is building to replace the International Space Station, gets significant publicity, but it’s the smallest part of Voyager’s business.

The largest and fastest-growing segment focuses on defense and national security: missiles, rockets, advanced hardened avionics, and deep application and involvement with programs like Golden Dome and Next Generation Interceptor. Firefly Aerospace is similarly positioned at the intersection of space exploration and national security. The company delivers rockets and satellites for the hardest missions, all to keep America first in space. “We’re doing a lot of great things to support our nation and keep ahead of the threats,” Kim says. “You’re going to see us contributing to big programs like Golden Dome and national security missions.” Kim sees the planets aligning for space, as the White House strongly supports the sector.

The Space Force, U.S. Space Command, NASA and the entire industry are growing toward a $2 trillion space economy by the end of the decade. “It’s a great place to start and grow your career,” Kim says. “I think in the future, every company is going to have something to do with space.” For graduates interested in venture capital, private equity or investment banking, the advice from these veterans is remarkably consistent: Excel in your current assignment first.

“Don’t even think about this world,” Madera says to cadets and young officers who reach out. “You’re in the Air Force now. You need to think about doing your current job the very best you can. You don’t just happen into this after you tread water for several years. It doesn’t work that way. You’ve got to be focused on being great and being recognized as a terrific contributor.” Wolfe agrees, and added, “My advice has always been to hit the ground running after graduation and be the best version of yourself during your time in uniform.” Kuta offers a counterintuitive perspective for those considering entrepreneurship. Starting your own company is lower risk than working for a corporation, he argues, because when you work for another company, strategic decisions five levels above you can eliminate your position without warning. When you start your own company and bet on yourself, you know exactly where you stand, he says.

“If you apply the grit and warrior ethos that you learn at the Academy to your own thing, then odds are you’ll have a much higher probability of success,” Kuta says. “The end product might not be what you thought it was going to be, and the duration might be faster or slower than you thought. But if you provide the tenacity and no-fail attitude, odds are you’ll find a way.” What most people say is their biggest fear about starting a company is running out of money, Kuta observes, but that’s not actually true. The real fear is putting yourself out there to the world, talking about how great your company will be and then publicly failing embarrassingly. “Most people are actually scared of that,” Kuta says. “It’s like an ego thing. So as soon as you can get over that, it’s much lower risk to go start and run your own company.” Most bankers and fundraisers will need an MBA from a top school to open doors, and timing matters too.

The economy needs to be strong for the market to be wide open, with banks hiring. For investment banking specifically, graduates should consider going to a Top 10 business school, if possible, or a regional business school, if focused on opportunities outside of core finance hubs. A few structured on-ramping opportunities come through veteran rotation programs at firms like Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan and Bank of America, among others. These programs offer training, mentorship and unique opportunities to help veterans transition into the financial services industry. Bank of America’s program is highly competitive and accepts only 15 candidates annually.

“Start laying breadcrumbs,” Sarkis advises. “Use the Skillbridge for an opportunity in investment banking or private equity. Work at a startup. Get certification exams. CFA is a good one you can do on your own time that is rigorous and respected. Show initiative and demonstrate you’re familiar with the work. It enables you to show people you’re a top-tier candidate.” The thread connecting all these graduates is resilience, as the Academy and Air Force taught them to persevere through challenges, maintain composure under pressure and keep their eyes on the mission regardless of obstacles.

“If you can get through the Air Force Academy, you come out really strong,” Kim says. “It allows you to be resilient against a lot of challenges you experience, both in your career and your personal life. It prepares you for being resilient and being able to get back up and learn from all of your challenges and just keep going forward.” Col. Wolfe puts it more simply. “Grit is the difference maker,” he says. “Everyone who earns an appointment has the smarts and athleticism to do great things, but it takes grit to survive, thrive and graduate from the Academy.” They’ve trained for pressure their entire careers, and an IPO is just another mission: Get to the target on time, execute effectively and bring everyone home safely.

“The best investment bankers become a trusted part of the community and an important thread in the very fabric of the ecosystem they serve,” Col. Wolfe says. “I wake up every day excited knowing I’ll make a positive impact on the sector.” In Times Square that June morning, as champagne sprayed and the team cheered beneath the image of the space station, Kuta felt that impact. This was a major milestone, but not the finish line. “An IPO is nothing more than a capital structure event,” Kuta says. “It’s definitely a great milestone and recognition of everything that the team’s accomplished. But we have a lot of work left to do.”