Checkpoints:

Mr. Jerome "Jerry" Bruni ’70

Distinguished Graduate Award Recipient

Mr. Jerome "Jerry" Bruni ’70

Jerome “Jerry” Bruni ’70 learned the meanings of sacrifice, service and grit at a young age. His upbringing included regular lessons in all three. A native of Portland, Maine, Bruni starts his story at the beginning. The setting: a six-unit apartment building owned by his paternal grandparents. “The apartments were small,” Bruni reminisces of his first home. “My grandparents lived in one of them, and they had five children who lived in the other five. So that was the environment that I grew up in for the first 12 years.” Bruni explains that his father, a first-generation Italian American, met Bruni’s Indian mother while serving in Asia during World War II. During his childhood, Bruni says, each day was much like the last. “I would wake up early and I would walk to our church where I was an altar boy and I would serve mass,” he says. “My grade school was very close so afterwards I would walk there, and then the next day we’d do it over, sort of like Groundhog Day. I was very fortunate to have a really caring family, and I had wonderful teachers. It was a very narrow experience, but one that I enjoyed greatly.”

Bruni’s experience grew somewhat less confined as he entered his teenage years — his parents saved enough money to purchase their own 1,000-square-foot house in a different area of his hometown, Bruni says. He also picked up an afternoon newspaper delivery route and worked summers shining shoes in his grandfather’s barbershop. “My parents wanted their children to go to the best public schools that were available,” he says. Bruni adds that he didn’t know anything about the nation’s service academies while growing up, but he did know that he loved science and wanted dearly to be an astronaut. “The Russians launched the first satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957, and that was major news,” he says. “It scared a lot of people, and I became almost instantly interested in astronomy, space travel, those sorts of things. I started a scrapbook, which I have to this day, and every time a satellite was launched or an astronaut went in space, I would clip that article out and save it.” Bruni did not, however, immediately equate space travel with military service. “My father served in World War II, but then again, so did almost every young male of that era,” Bruni says. “Beyond that, I had very little familiarity with the military.” He adds, “In the mid-1960s, when I was coming to the Academy, there must have been a million young teenage boys who wanted to be astronauts, and I was one of them. In looking through their catalog, the Academy seemed to be a very interesting place, a challenging place, and that’s what I wanted.”

FOREVER A STUDENT

As far back as he can remember, Bruni’s parents placed great importance on education. That passion for learning has followed him his entire life. “I think that stemmed from when I was perhaps in the second grade,” Bruni says. “When my parents went to the grocery store, they would come back with a paper bag, and my mother would take a pencil and write on the paper bag numbers like ‘378, 412, 914’ and draw a line, and she’d say, ‘Add them up.’ Over time, she would write longer and longer numbers, and I would add them. For some strange reason, it was just fun, and it really made a difference. I never would have been able to go to the Air Force Academy were it not for the academic preparation and the education that I received.”

When it eventually came time to consider institutions of higher learning, the process was brief. “I was doing some research on possible colleges, and I started with the letter A, and the Air Force Academy was there. I didn’t get much further,” he says, adding shortly thereafter he flew into Colorado for inprocessing, but his connecting flight from Denver to Colorado Springs was overbooked. “The Academy sent a big bus up to then-Stapleton Airport and a whole bunch of new Academy appointees got on and drove down to the Academy. I remember someone pointing out the window and saying, ‘Oh, there’s the chapel!’ We all got really excited.” Bruni says getting off the bus was a “shock.” “I had no idea what the Academy experience was about, other than it was a beautiful place and they had wonderful programs,” he says. But Bruni admits, due to his limited life experiences while growing up, traveling alone to the Academy was a tense experience. Prior to arriving in Colorado Springs, Bruni had flown only one other time. “After my parents were married, they saved for about eight or so years so that my mother, my sister and I could go [to India] and visit her parents,” an emotional Bruni recalls. “That was the one and only time that I saw her family.”

AN ‘ACTION-FILLED’ EXPERIENCE

Standing less than 5'6" tall and weighing 110 pounds at inprocessing, Bruni says, physically, the Academy presented a great number of challenges. One of his earliest memories of the institution involved dealing with the high wind. “The doors to the dormitories are tensioned so that they don’t blow open,” he explains. “I remember opening one of those doors and saying, ‘Are all these people supermen? Why are these doors so tight?’” He also explains that the gear cadets carry on marches and runs weighs the same whether one is a Falcon football defensive lineman or an aspiring astronaut from New England. But Bruni found his inner athlete at the Academy, adding his favorite sport was squash. “Squash is played low to the ground, and I am low to the ground,” he quips. “So that was a natural advantage. I also played soccer and boxed, believe it or not. We had to have somebody in the very lightest weight division, which was me.” Bruni says he remembers a bout with a classmate who went on to win the Wing Open. “He came out with a very unconventional style, and I thought, since I had already taken boxing in PE class, that I was prepared and whatnot — but he was more prepared, I can tell you that,” Bruni says. “But what I took away from all of that, in my view, is confidence.”

Bruni also recalls the now-infamous May 31, 1968, F-105 Thunderchief flyover. The sonic boom from that event shattered windows across the cadet area. “In retrospect, seeing them flying in and not hearing them was simply evidence of the fact that they were flying faster than sound,” he says. “It didn’t dawn on me until they went over and there was a big boom and the sound of all that glass….” Bruni says cadets were at the noon meal formation at the time. “Thank goodness,” he says. “As cadets, we saw lots and lots of flyovers. Had we been in the dorm, this one would have been somewhat tragic.” Upon returning to their rooms, cadets found shards of glass lodged in the dorm room doors, Bruni says. He also recalls far more typical events, such as participating in various intramural sports, marching in parades and attending Falcon football games. “It was a very intense, action-filled experience,” he says. “I enjoyed it.”

UNWAVERING COMMITMENT

Bruni says he learned a lot from the military and athletic training at the Academy, but science and mathematics remained his passion. “I was hyperfocused there,” he says. “I knew there was a military component. I didn’t give a second thought to the athletics. I didn’t realize that I’d be as active as I was, but I was certainly more focused on being an astronaut.” Unfortunately, Bruni ultimately was not pilot qualified, cutting short his dreams of space travel. “I originally thought I would be a math major,” he says, “but I found economics, which is heavily math-intensive, to be far more interesting. So I picked economics, and my particular application was operations research, and I really enjoyed that, and I practiced it in the Air Force. “Economics is how we live our lives,” he adds. “It’s how our society is organized. It’s not laid down by government edict, but rather people independently do things, pursuing their own interest, and in so doing, create a wonderful, broad and diversified economy.”

While heavily focused on numbers as a cadet, Bruni says it was impossible to ignore, as graduation neared, the geopolitical climate into which he and his classmates were commissioning. “I realized at the time going to Vietnam was a possibility,” he says. “We would hear some war stories from our instructors, for example, our AOCs. But beyond that, it was such a busy time. Wearing a uniform in the mid-’60s — it’s hard to imagine nowadays, whether people agree or disagree with how the military is used, most people thank you for your service and have a positive view toward people in the military. But that wasn’t the mid-’60s. Those in uniform were treated sometimes disparagingly.” But Bruni never questioned his commitment. “Service is important. I mentioned earlier that when I was a young boy, I would get up and go to church and serve mass,” he says. “That’s an element of service. And, you know, it felt good. I certainly couldn’t tell you then why it felt good, but it felt good. And in all my years, whether I was in the Air Force or out, when I’m in a position to serve others, that’s a very rewarding thing.”

BEYOND THE ACADEMY

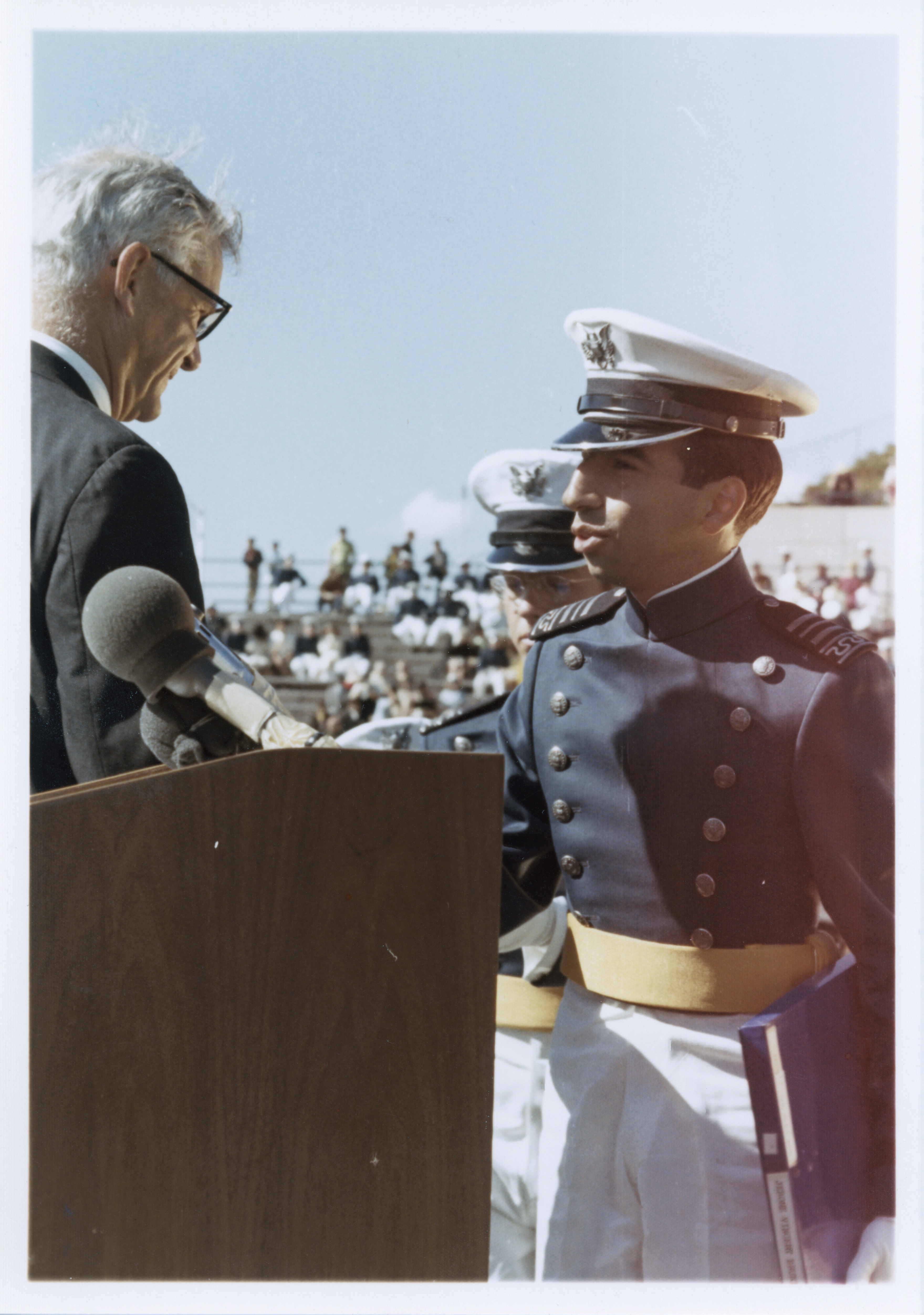

The graduating Class of 1970 entered Falcon Stadium on a cool, late-spring morning. The sun broke the chill and warmed the crowd as then-Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird delivered the commencement address. Bruni, along with the other 744 graduates that day, threw his hat into the thin Academy air. Just more than a week later, he set off — not for Vietnam but for graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles. When he arrived at UCLA, Bruni worried he might be behind peers who didn’t have the time demands of a service academy. “There was no need for that,” he says. “The Academy preparation was excellent. We were able to fit in very easily, and it went well. … In my case, I was very thankful for the Academy background and experience.”

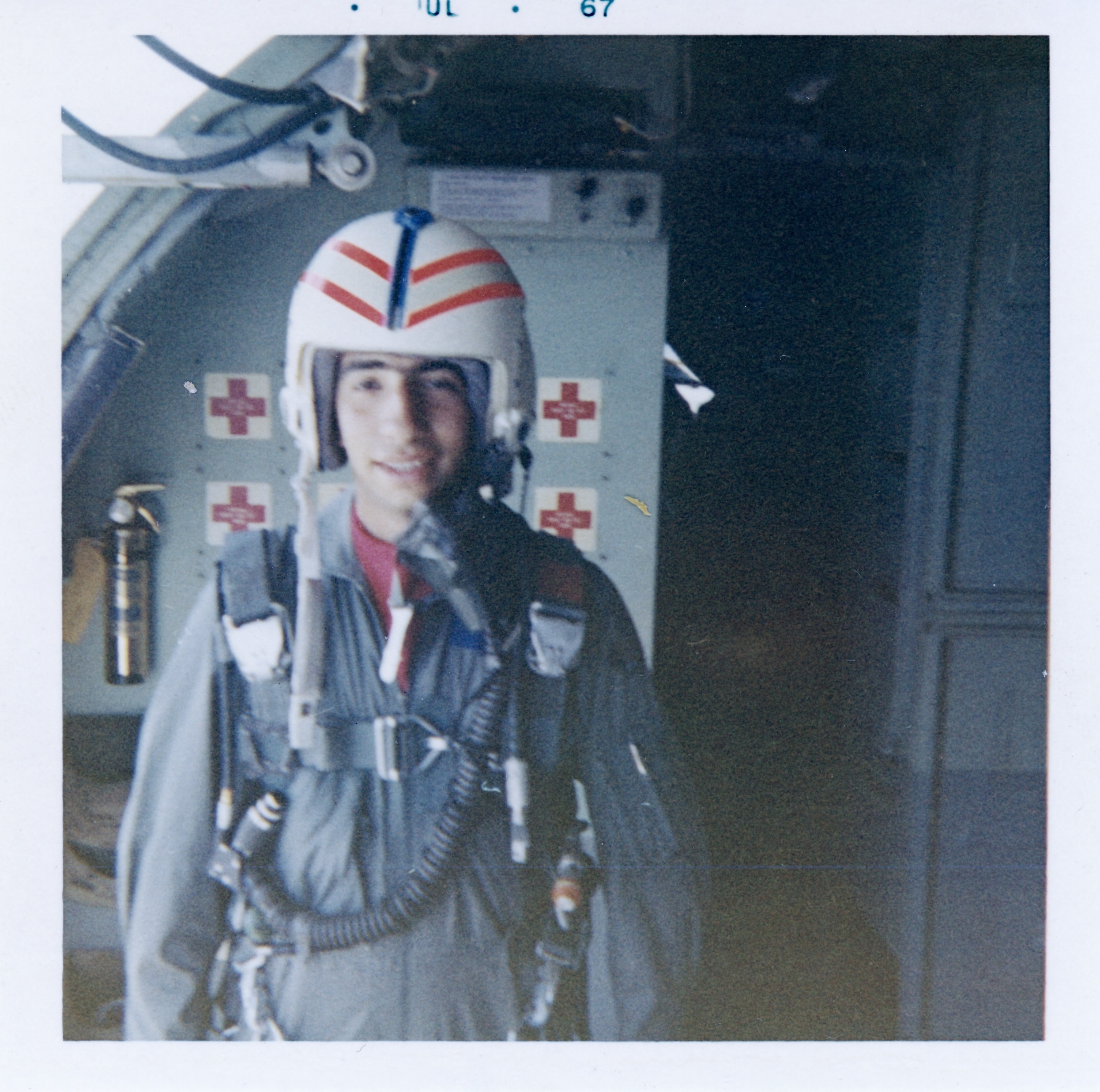

Following graduate school, Bruni went on to an Air Force Systems Command laboratory, at the time called the Rome Air Development Center. He was then stationed with Pacific Air Forces in the Philippines, where he worked in a squadron that evaluated deployed F-4 aircrews. “We would fly instrumented drones that the aircrews would try to shoot down,” he says. “And we would try to learn what works and what doesn’t work and provide that experience and feedback for the aircrews. From there, I worked for the Defense Nuclear Agency in modeling theater conflicts. And then from there, I came back to the Academy.” For five years Bruni continued to serve his nation and support a new generation of cadets as a USAFA instructor. “It was a great deal of fun,” he says. “If there’s anything that I learned, it was that teaching is an excellent learning experience. By preparing, by responding to the questions from the students — and the students had many questions that I hadn’t anticipated — that helped me develop my understanding of the subjects that much better.”

Bruni says the one thing that changed the least since he attended the Academy was the cadets. “The cadets are still the eager, aspiring, questioning young men and women nowadays that they’ve always been,” he says. “They are a very impressive group. I have invariably been impressed.” While at the Academy the second time, in 1983, Bruni married his wife, Pam (whose father had been a colonel in the Air Force) and soon adopted her two young sons. With 14 years of service under his belt, he decided to separate from the military. “It became obvious that the best thing for the children was to stay in place for a while. So that’s what led to my leaving at that time. Not too many people leave at that point,” he says. “Usually it’s much earlier or much later. I went to work for a Wall Street firm, and again, as with my experience at graduate school, the preparation at the Academy was really key. It made things much easier than they might have been.”

PAYING IT FORWARD

In 1992, Jerry and Pam began the Bruni Foundation. The decision, over the subsequent years, has impacted countless lives. “We realized that when we wanted to give to nonprofits was not necessarily the best time financially to do that giving,” Bruni says. “So by giving to the Foundation, we could give as we felt we could, and then we could parse it out as opportunities presented themselves.” Bruni says the inspiration was simple: He and Pam found joy in positively influencing their communities. “We want to help [people] reach their aspirations and to be able to be full and productive members of our society,” he says. “So that which we can do to help people in education, whether it’s academic education or vocational education, strikes us as very worthwhile investment, and that’s how we think of it, as an investment.” The foundation has gone on to send dozens of Colorado Springs high school graduates on to higher education opportunities free of charge. In Bruni’s hometown of Portland, Maine, the foundation supported a hospital that developed a children’s mental health program. “That hospital is the hospital that I was born in,” Bruni says. Portland’s Boys & Girls Club has also adopted vocational programs, thanks to the foundation.

Recently, the Brunis created an endowment with the Air Force Academy Foundation to reduce some reunion costs for younger graduates and create regular opportunities for connection and engagement. “I have attended reunions, living here in Colorado Springs,” he says. “I attend all of them, and it’s a great opportunity. And I just wish that more graduates would have that opportunity, and in doing that, develop ideas of how they’re going to contribute, how they’re going to help the next generations.” Bruni explains that during one reunion, classmates decided they wanted a way to remember those who fought and died in the Vietnam War. “We thought, ‘This is a story that others need to hear,’ and from that, we developed a program to build the Southeast Asia Pavilion,” he says. “We just felt strongly about it, and we came together to that determination when we were physically together.”

Bruni also occupies his time these days serving as an overseer (like a trustee) at Stanford University’s think tank, the Hoover Institution. “We go there and are briefed by leading authorities in many, many fields, one after another after another. It’s wonderful,” he says. And Bruni’s service to the Academy continues. He has found his time serving on the Air Force Academy Foundation Board of Directors as a founding director “vastly more interesting than I ever imagined. My experience on the board … has been remarkable. I’ve met so many very interesting graduates from different backgrounds who have just a large number of ideas that other people can learn from and who are really engaged. It’s infectious.”

PERSEVERANCE AND TEAMWORK

Bruni, looking back at his life and career, pinpoints some defining moments. “In my personal journey, marrying Pam was certainly up there. When you have a family, you progress as a family. You do things as a family. So that was very important,” he says. “And beyond that, the Air Force presented a steady progression of opportunities, and through every one of them, I was able to learn something new that’s applicable in life.” And Bruni points to the perseverance and teamwork he learned while at the Academy as life lessons he’s carried with him since graduation day. “The teamwork aspect is important,” he says. “It takes time to develop a means of working with people. People are not all the same. They don’t think the same, they don’t react the same. And you’ve got to take the time to understand how to engage with all of your teammates, different as they may be.” Bruni adds, upon learning he’d been selected for the Distinguished Graduate honor, that he “threw my hat in the air all over again, and I wasn’t wearing a hat! I was just thrilled.” He offers his thanks to Brig. Gen. Curtis Emery ’70 — who nominated him for the honor — along with all his classmates.

“First and foremost, if it weren’t for them, I never would have graduated,” he says. “If it weren’t for them, I wouldn’t have survived a year. They have always been there; they’ve always lifted me up. I’ve tried to do my part, but they did more than I did.” Bruni also has advice for himself as a newly commissioned Air Force officer if he could go back in time. “The advice that I would give myself as a recent graduate is to realize that I had lived a somewhat cloistered experience,” he says. “The world is a very broad place; the Air Force itself is a very broad place, and there’s so much to learn. If you think about what you’ve learned in the 10 years up to graduation — this would be from ages 12 to 22 — that’s a lot, and there’s a tendency at 22 to think that you’ve done it all. But the next 10 years are going to be just as interesting and just as filled with learning experiences.”

Bruni also shares what it means to be part of the Long Blue Line. “The Long Blue Line represents, in one word, continuity. It’s a tremendously important concept that we are connected from the earliest class of 1959 through the most recent class, 2025,” he says. “That’s a very reinforcing feeling.” Finally, Bruni explains his “why” — for attending the Academy, for serving his nation, and for impacting the lives of so many people he’s never even met. “I think the opportunities to serve at the Air Force Academy are opportunities to understand how important the concept [of service] is. It’s easy to say, ‘Well, that’s a service academy,’ or ‘You’re in the service,’ but the actual participation, which is so rewarding, you really need to do it. And in doing it, it becomes self-reinforcing.” His “why” is a message he hopes resonates with today’s cadets. “The most rewarding thing is service itself,” he says. “If you get a new award, a new car, a new experience, sooner or later, it’s going to lose its luster. But the experience of service is one that is forever rewarding and forever exciting.”